Photos, Life Timeline, Articles, Poem Recovery

Part I. Introduction

(The content of this blog is a duplicate of my other blog, "Winifred Virginia Jackson--beyond Lovecraft". I created this one due to problems that I had in posting that blog.)

Winifred Virginia Jackson (1876-1959)—Life

Event Timeline, Interviews, and Poem Recovery

As a fan

of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu, I stumbled across the name of Winifred Virginia

Jackson. She, due to her beauty and mysteriousness, intrigued me to the point

where I resolved to find out more about her and share it with anyone

interested. I further resolved to collect samples of her works and share those

too because only smatterings of her poetry appear here and there. My meager collection of her life’s details

and her poems is contained in this site.

This

blog is presented in 4 parts. It has 6 photos. Part I

is this introduction. Part II is a timeline of her life, some

life events, and whereabouts. Part III

is a collection of 4 articles about her during her period of greatest

recognition and celebrity—1920-1921—arranged in the order in which they were

written. As you read these articles, please note how the authors all seem to

have a hard time dealing with her unexpected beauty and sophistication. They

keep mentioning her as a girl, even though she was 44 at the time and twice

divorced. They also provide details of her peculiar method of composing her

poetry. They hint at her large output of poetry as well, much of which has

almost certainly been lost. One of the articles provides the categories of

poems that she wrote, as defined by H.P. Lovecraft. These articles probably

provide the best insight into her as a person, but perhaps her poetic work

could provide some insight as well. Part

IV is a collection of her recovered poems; 95 were found. When compared to

the fact that she claimed to have written 49 poems in 3 days, these recovered

poems plus 76 other published titles do not seem like much of a collection. It

could be that these 95 + 74 poems (actually, 72 because two of the titles are

short stories) were her best efforts because these were the ones that got

published. The poems are preceded by a list of the recovered poems followed by

a list of poem titles that were known to have been published but which could

not be found. These two lists are arranged roughly in the order of their discovery

and are followed by the (95) recovered poems.

As you read her poems, it helps on some of

them to realize that Great Pond is her Maine hometown, and the town of

Ellsworth is about 40 miles south of Great Pond. Great Pond is a very rural

place, and this explains her expertise in using rural dialect in some of her

poetry. Great Pond had a population of 58 in 2010. A few of her poems refer to

Great Pond and its residents and surrounds. A flyer that attended her first

book publication, Backroads Maine Narratives, With Lyrics, states, "Winifred Virginia Jackson was

born in the Williams Settlement (named after Joshua Williams, Winifred’s great

great grandfather.), Township 33, at the head of the Union River, thirty-odd

miles from Bangor, Maine.” (“Township 33” should really be “Plantation 33”.

“Plantations” in the state of Maine are rural areas which are designated as having

potential to become towns. Plantation 33 incorporated into Great Pond in 1981.)

Her parents were father John Kingsbury Jackson, a lumberman, and mother Myra

Evelyn Williams. A couple of her poems refer to “K-J”, which is a reference to

her father, Kingsbury Jackson. A brief family tree available on the LDS website

shows that there were other siblings in her family: Guy Jackson, 1872-1880;

Ralph Temple C. Jackson, 1879-1957, and Direxa Myra Jackson, 1885-1885, and of

course, Winifred herself, born March 3, 1876.

Winifred

Virginia Jackson was an amateur poet whose period of greatest poetic output

occurred from about 1916-1927. She was born in a rural logging area of Maine

and came to the Boston area in her teens. Her first marriage was in 1902 to a

salesman, and he is probably the person with whom she traveled the country from

1902 to around 1910-1911. She started

writing poetry in California in 1910, but from this poetic beginning to about

1915-1917 she threw most of her poems away until a critic convinced her

otherwise.

I

arbitrarily name the time that she was associating with HP Lovecraft her

“Lovecraft Period,” which was from 1915-17 to 1921. They both were good friends

with common literary interests during this time. It is documented that in 1918

she sent him a copy of “The London Daily Mail”, a British tabloid, and also

sent him a portrait of herself in 1920. The first of this gifting occurred in

1918 while she was estranged from her second husband, Horace W. Jordan. The portrait gift prompted HP Lovecraft to

compose the following poem to Mrs. Elizabeth Berkeley, a pseudonym of hers.

That Lovecraft thought she was very beautiful is proven by the poem that he wrote

for her upon receiving that portrait from her as a Christmas gift. The poem

follows:

“On

Receiving a Portraiture of Mrs. Berkeley, ye Poetess” by HPL, Christmas, 1920

As

Phoebus in some ancient shutter’d room

Bursts

golden, and dispels the brooding gloom,

Drives

ev’ry shadow to its lair uncouth,

And with

bright beams revives forgotten youth;

So ’mid

the centuried shades of Time’s retreat

See

radiant BERKELEY rise in counterfeit!

A score

of ghosts, dim dreaming thro’ the night,

Start

sudden at the unaccustom’d light;

From

dusty frames the white-wigg’d rhymers stare

In

quaint confusion as they hail the fair.

Here Goldsmith

gapes, half-doubting as he views,

Whether

he sees a goddess or a Muse;

Waller

close by, a jealous look puts on,

To see

his Saccharissa thus outshone,

Whilst

Pope inquires if in this sight there gleam

Indeed a

poet, or a poet’s theme!

But now

another bard insistent call;

Blest

Hellas’ train, each from his pedestal;

See

Venus and Minerva spiteful vie

To have

the new arrival settled nigh.

Graces

and Muses in contending songs

Advance

the merits of their rival throngs,

Till

Jove rebukes them with a thund’rous oath

For

claiming one who is ally’d to both!

Now

speaks that leader who with light divine

O’er all

the pantheon can in splendour shine;

The

Delian god, to art and beauty bred,

Who

wears the laurel on his golden head:

“Cease,

trifling nymphs, as equals to protest

To one

whose gifts so much excel your best;

Tho’

outward form the fair indeed would place

Within

the ranks of Venus’ comely race,

Yon

shapely head so great an art contains

That

Pallas’ self must own inferior strains.

If one

fair object be a thing to shrine

In

marble fanes, and worship as divine,

How may

we judge the mind whose magic pow’r

Creates

new worlds of beauty ev’ry hour?

As Venus

fair, but as Athena wise,

New

honours wait a BERKELEY in the skies;

Blest

with vast beauties that are hers alone,

She

claims from us a new exalted throne.

Let none

dispute her place, but let her shine

Impartial

o’er the Graces and the Nine!”

He

ceas’d, and all the heav’nly train obey’d,

Whilst

the new deity dispers’d the shade.

The

grave old bards around the study hung

Straighten

their wigs, and labour to seem young.

Author

and god alike acclaim her might,

And

sculptur’d fauns approve the pleasing sight:

So the

whole throng the novel wonder bless—

At once

a poem and a poetess!

I have

included a very poor copy of a photograph of Winifred at the seashore in 1918

taken by Mr. Lovecraft. Lovecraft scholar, S. T. Joshi, believes that their

relationship never went deeper than friendship and gift exchanges, in addition

to collaborating on a couple of stories. I agree with his assessment.

Although

an amateur poet, Winifred Virginia Jackson was a working woman. She worked at

different jobs throughout her life, and is recorded as working as a secretary

at age 68 in 1944. Most of the time, her jobs were as secretary, stenographer,

and editor. During 1922-1929, however, she became a co-founder and eventual

owner of B.J. Brimmer Publishing Company, in which she served as its treasurer.

This company went bankrupt in 1927, and perhaps remained viable until 1929.

Oddly, even with her long work history, she never applied for Social Security

(which started in 1935) although she worked at least until 1948. Given the low

paying nature of (most of) her jobs, the low pay that women usually received,

the Great Depression, and the continuous need to work, I speculate that money

was usually in short supply for her.

Somehow

she got the reputation of once having had a black husband, and even during her

lifetime was said to be black herself. It is unknown if this rumor was

widespread or not. Most discussions about Winifred Virginia Jackson mention her

relationships with her husband, Horace Wheeler Jordan, and her alleged lover

and business partner, William Stanley Beaumont Braithewaite. Both of these men

are mentioned as being black men (except that Horace Jordan was white, and the

popular literature is wrong which is proven in the next paragraph), which in

our times is not worth mentioning. But

back in the 1920s when racism was more extreme and widespread, writers should

and do mention these relationships because such a detail could give some

insight as to her character; i.e. she was more than willing to violate the

norms of her time and deal with the consequences. I have not read any of

Lovecraft’s letters which give his reaction to discovering that Braithewaite

was black (but I read about it), and do not know if there is any documented

Lovecraft reaction to her marriage to Jordan, whom some say was black, but as

you will see, the facts will show that any extreme reaction due to the blackness

of these men is overdone.

First of

all, basic research shows that her second husband, Horace W. Jordan, was white

(as was her 1st husband, Frank Le Monn). This conclusion is based on

his birth record listing him as white, the 1910 census which lists both him and

his parents as white, his 2nd marriage in 1921 which shows him as

white, and his 1917 draft registration which lists him as white. Furthermore,

the 1913 marriage record for him and Winifred Jackson has a spot to list

“color, if other than white”, and it is not filled in for either of the pair,

indicating that the marriage was nothing out of the ordinary, racially

speaking. Horace was living at home as a 32 year old only child with his

parents in the 1910 census. Living with them was an Irish servant who had

immigrated here in 1906. His father, age 61 at the time of the 1910 census,

lived off his “own income” and the father of Horace’s mother was born in

England. These are unlikely

circumstances for the normal black family of this time in racist America.

William

Stanley Beaumont Braithewaite was Winifred Virginia Jackson’s business partner

and founder of B.J. Brimmer company. The 1920 census lists both he and his wife

(and consequently all of his children) as “Mu”, meaning mulattoes. Photos of

him show him to be of dark Caucasian appearance. His 1917 draft registration shows that he was

initially categorized as white, and this was then blacked out and “Negro” was

checked. Back then, and to some extent now, most people considered anyone of

mixed race to be Negro, regardless of percentage. For example, in Samuel

Clemens’ novel, Pudd’nhead Wilson, slave owners viewed people who were

of just 1/32 Negro heritage as black. It is alleged that Winifred Virginia

Jackson had a multiyear affair with Mr. Braithewaite. I will await some sort of

evidence that this may be so, such as revealing statements from Mr.

Braithewaite’s papers. I tend to believe that there was an affair. If there was

such an affair, it probably ended on or before 1934 which is when he moved with

his family to Atlanta to become a college professor.

This

brings us to the final “black theory” about Winifred Virginia Jackson, which is

that she herself may have been of mixed race. Please read the following excerpt

from page 183 of Colored Girls’ and Boys’ Inspiring United States History

and a Heart to Heart Talk about White Folks by William Henry Harrison, Jr.,

a black man, copyright 1921. This whole book can be found on the internet at:

“All

verse critics who regularly read the close-to-nature, true-to-life,

heart-to-heart and cheerful little poems that weekly head the editorial pages

of the Chicago Defender, join in acclaiming Alfred Anderson the Edgar A. Guest

“Sunshine Poet” of the Negro Race. A few of the many other colored verse

writers whose poems frequently appear in leading magazines are Carrie C.

Clifford, Sergt. Allen R. Griggs, Jr., Thos. M. Henry, Sarah C. Fernandas,

Leslie P. Hill, Roscoe Jamison, Chas. Bertram Johnson, Winifred Virginia Jordan, Will Sexton and Lucian B. Watkins, the

last named writer being considered among the foremost writers the race has produced during the past few years.”

The

format of Mr. Harrison’s book is to list as many accomplished and high

achievement negroes as possible for each field of endeavor, e.g. sports,

poetry, writing, music, diplomacy, politics, military, religion, education,

business, law, etc. as well as impactful negroes of American history. To this

end, the book sometimes lists whole pages of names of accomplished negroes, far

too many to have been vetted as to whether they are truly black or not. Had Mr.

Harrison resided in Boston and not in Pennsylvania in 1921 and given his

interest in poetry (his book is sprinkled with his own poetic creations), then

I would say that his racial claim about WVJ most definitely deserves

investigation. But, due to the geographical distance between him and her and

due to the hundreds if not thousands of other names in his book, his inclusion

of her on his list of black poets is very likely incorrect. The probable origin

of his claim is due to at least 5 of her poems being published in various

issues of the Brownies Book and 4 other poems published in various issues of

“The Crisis” which were periodicals published by blacks, for blacks—the

“Brownies Book” was for black children, and “The Crisis” was for adults. One of

the founders of both periodicals was W.E.B. Du Bois, the famous black

intellectual. (I do not know if WVJ ever met Mr. Du Bois.) So, one’s thinking

might be that if these periodicals are published both by and for black people,

then for sure the editors would use only black contributors in them. Wrong –see the following paragraph. It may also be that her alleged lover and

business partner, William Stanley Braithewaite, himself a mulatto and influential

in literary circles, could have had some influence in getting her poems

published in these black periodicals. However, she got her poems published in

these two black periodicals before

her known association with Mr. Braithewaite and during her years of high praise from the racist Mr. Lovecraft. Thus

it could be that she got those 9 poems published on her own.

I also

stumbled across the same racial claim as William Henry Harrison Jr.’s made by

MIT bachelor’s degree candidate Robin Patricia Scott in her thesis on June 2,

1986, entitled “Being Black and Female:

An Analysis of Literature by Zora Neale Hurston and Jessie Redmon Fauset” and

dismissed it out of hand for the same reasons listed previously. Inspection of

the document shows that Winifred Virginia Jordan’s (Jackson) poems appeared in

4 separate issues of “The Crisis” and this was the source of this incorrect

information. Winifred’s name appears in the Appendix of the thesis which

contains a list of female authors who published in “The Crisis”. Regarding

these authors, the author of the thesis,

Ms. Scott, writes “I have placed stars next to the names of women who I know

are black “, but she never reveals how, in 1986, she knew that. (Winifred's name has a star.) Could she have

read William Henry Harrison, Jr.’s book which was incorrect about WVJ?

Apparently not, for Mr. Harrison’s book is not listed in the bibliography.

However, Zora Hurston and Jessie Fauset, who were both contemporaneous with Ms.

Jackson, died in 1960 and 1961, respectively, but theoretically could have left

a record of whom they recalled as being black. Three of Winifred’s poems were

published in “The Crisis” in 1920, and the 4th in 1921. The work of

Hurston appeared in 1925-27 and Fauset’s in 1919-1923, plus Fauset was literary

editor of both the “The Crisis” and “The Brownies Book” during the time of

publication of Winifred’s 9 poems. So Fauset would be the more likely source of

the story that WVJ was black.

If one

looks into WVJ’s family genealogy, one can see that she has one of the most

lily-white backgrounds one can imagine, although it is not impossible for her

to have had some racial mix. All four of her grandparents were censused as

being white. I did not even try to investigate her great grandparents. So

hypothetically, if just one of her 8 great grandparents was black (or if one of

her 4 grandparents was half black, passing as white), she would be 12.5% black

(an octoroon). She herself always listed

herself as white, and you can see the photographs in this document in which she

appears to be white. Clearly, the weight of the evidence is on the side of

white, not black. Thus it is time to set the record straight on this matter and

disregard it forevermore.

Her life

story indicates that she was comfortable in black literary society and she

likely did have an affair with her business partner, Mr. Braithewaite. That is all. These stories about her and 2nd

husband Horace, I repeat, are probably a result of her poems frequently being

published in black periodicals and her alleged affair with Braithewaite, a man

of mixed race.

In 1922,

she and William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite started B.J. Brimmer Company, a

publishing house which bankrupted in 1927-1929. One of her duties at the time

was that she was treasurer and I’m sure an editor as well. This publishing

house published the aforementioned Backroads: Maine Narratives, With Lyrics,

in 1927. She had prior publishing and editing experience in 1919 with the

publication/editing of “The Bonnet.”

In 1944,

Selected Poems by Winifred Virginia Jackson and Ralph Temple Jackson was

copyrighted and published on May 3, 1944. This was the 2nd and last

of her two books. This “book” is only 10 pages, contains 7 poems, of which 4

are WVJ’s, and are reproduced herein. No bios or photos. These 4 poems show

that her poetry muse still had not left her, although it was apparently not

nearly as productive.Winifred is listed as the co-author, but it appears as

though Ralph Dighton Jackson of Boston, daughter of Ralph Temple Jackson

(Winifred’s brother and architect by trade) was the compiler. Winifred was

around 68 years old in ’44.

Most of

our knowledge of her comes from what I call her “Lovecraft Period” of 1915 to

1921, and the “Braithwaite Period” of 1922-~1927. William Stanley Braithwaite

was a well known critic, anthologist, and writer. Braithwaite was married in

1903 and had 7 children. Lovecraft was

impressed with her as a writer and always was complimentary about her poetic

contributions submitted under her name Winifred Virginia Jordan while being

married to Horace Jordan, and then afterward for about a year through 1920

under her maiden name, Jackson. As to her main body of work, it appears to have

been published between 1915 and 1930 in several soft copy pulp literary

magazines. In 1930 she published “The

Slip Up”. This is a short story (i.e. prose), and is only one of two that she

had published. She did, however, collaborate with HP Lovecraft on two of his

horror stories entitled “The Green Meadow” and “The Crawling Chaos”, plus she

was given credit by Lovecraft for a short story, “The Unknown” under the

pseudonym “Elizabeth Neville Berkeley”, which it is believed that he himself

wrote based on a dream of hers. After 1930, she had a few poems published which

I did not see in the earlier anthologies which indicates that she still wrote

some poetry on occasion.

Here is

another thing we know about Winifred. Some people say that a woman’s

prerogative is to change her mind, but a lesser prerogative could be to lie

about her age. Winifred Virginia Jackson lied a lot about her age. What follows

is a list of date events which required a person to state his/her true age. Her

true chronological age (calculated from her 1876 birth year) is also listed.

One can only speculate on what age, if any, she provided to HPL in her

“Lovecraft Period” of ~1915 to 1921. After all, she was 14 years older than he

was.

Event Stated Age True Age

1900 census 21 24

1902 marriage 22 26

1910 census 27 34

1913 marriage 29 37

1920 census 28 44

1930 census 38 54

Because

her poems were published in an assortment of different literary magazines, it

is hard to get a complete grasp on her body of work, but it is considered to be

large. Unfortunately, most were published in soft cover pulp literary magazines

which throughout the pulp era (~1890-1950) were considered beneath the

attention of most libraries, universities, and bookstores; some of the issues

certainly have not lasted into modern times. Those that do survive can sell for

$20 on up to several hundred dollars. This scattering and surviving rarity

makes it appear as though she wrote many fewer poems than she actually did

write. Her surviving descendants might have a collection of her work, but who

knows? She never had children, and her niece, Ralph Dighton Jackson, who was

interested in publishing poetry and

short stories and also ran poetry workshops, never had any either, but there

are other relatives around who still might have a big collection of her output.

I am not

a poetry critic, but I do like her poems. It is hoped that this collection of

her work will show people that Winifred Virginia Jackson, whose only modern

claim to fame is her contact with the great HP Lovecraft, deserves to be

recognized as a significant talent on her own.

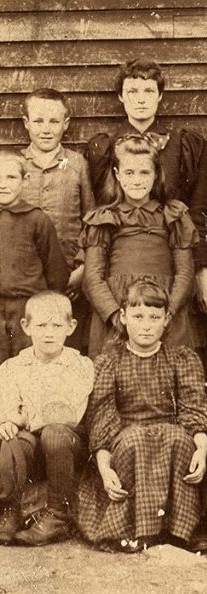

Ralph and Winifred Jackson,

3rd row back, Great Pond School,

September, 1893

Part

II. Winifred Virginia Jackson TIMELINE

1876- Birth- 3/3/1876 in Great Pond, Maine. It was founded in

the early 1800’s by Joshua Williams, Winifred Jackson’s great great

grandfather. It was a lumbering town. In 2010, it had a population of 58.

~1879- Older brother Guy Jackson, b. 1871-1874, dies. Winifred is about 3 yrs old.

1880- Census—Jackson family living with wife Myra’s parents:

Asa Williams and Direxa Williams in Great Pond, Maine. Asa and Direxa have

their 6 unmarried children there, 2 boarders, and the 4 member Jackson family

for a total of 14.

1893- Attends Great Pond School with brother Ralph. School

roster lists her as “Winie Jackson.”

1893-1895- Sometime during this interval, Winifred moves to

Boston while “in her teens”. After the relocation to Boston, she attends the

School of Expression, now known as Curry College, on Commonwealth Avenue in

Boston and also Eastern State Normal School. Unknown if graduated.

Pre-1899-Parents Myra Williams and John Kingsbury Jackson

divorce. In 1899, he marries a woman 23 years younger and moves to New Hampshire.

1900- Census—Works as a stenographer while as a lodger in

Northfield, Massachusetts. Northfield is 80 miles from Boston.

1902- 1st marriage --on June 21, 1902 to Frank M.

Lemmon (1869-1948) in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

He lists his name as “Le Monn”, although his brothers use “Lemmon”. He is a salesman. She lists her occupation as

a stenographer. She lives in Boston.

1902-1910- Travels and lives in various USA locales

including Seattle, Midwest, New Orleans, Aiken, S.C., and Norfolk, VA. She claims to have studied music, singing,

and dancing.

1910- Starts writing poetry in California.

1910, April- Back living in Suffok County, MA (Boston and

surrounds) with mother Myra. Census shows her using married name of LeMonn.

1911 estimated- Divorce from Frank M. Le Monn. No record found. Between 1911-1913, begins

re-using maiden name of Jackson.

1913- 2nd marriage-- to Horace Wheeler Jordan on

August 14, 1913. Between 1913-1921,

while using last name of Jordan, investigates possible land reward to Joshua

Williams, her great grandfather, as appreciation for his revolutionary war

service.

1915- Father Kingsbury Jackson dies in New Hampshire at age

70.

1915- Begins frequenting same literary circles as HP Lovecraft. Both have contributions published in “Dowdell’s Bearcat”, a pulp journal, Dec, 1915 issue. This association lasts until late 1921. Begins having some of her poems published in pulp magazines and newspapers.

1915- 1st husband Frank M. Le Monn convicted of

swindling and conspiracy and sentenced to 1 year and 10 days in the

penitentiary. Case receives national news coverage, and was about selling

fraudulent stock in the United States Cashier Company, a company started in

1902 and headquartered in Portland, OR, where he was sales manager. He was the

only defendant of several who had fled arrest and was apprehended in Toledo,

Ohio, after a pursuit over half the country. He allegedly profited $90k from

the scheme.

1919- Living in Boston area (Newton, MA), with husband Horace

W. Jordan and mother Myra.

1919, June- Edits and publishes “The Bonnet”, vol. 1, as Winifred Virginia Jordan, 12 pages, which

contains two of her poems and two unsigned contributions from H.P. Lovecraft.

~1919- Divorce from Horace W. Jordan. No record found.

Begins re-using maiden name of Jackson in 1920.

1920- Jan 16- Census—Works as a stenographer in Boston area.

Lives with her mother and uses the name of Jordan, but is listed as “single.”

1920-1921- Enjoys her period of greatest celebrity and recognition

as a poet, with at least 4 separate articles written about her in various

publications. Four found articles are reproduced herein.

1921- Last known contact with HP Lovecraft late in this

year. In a 1921 article contained herein, claims to have been advised by a

critic more than 4 years prior to stop throwing her poems away.

1922- Lives in Boston with mother Myra Williams Jackson.

Occupation:”writer”.

1922- Becomes a co-founder of BJ Brimmer Company with

William Stanley Beaumont Braithewaite. He apparently is the driving force of

this new publishing company while she

serves as part owner, an editor, and treasurer. Becomes full owner in 1925 in a

period of financial difficulty for the company.

The company specialized in publishing poetry anthologies, in which many

of her poems appear.

1924- Living in Boston area.

1927- BJ Brimmer Company publishes Backroads: Maine

Narratives, with Lyrics, the first of two books published by her as an

author in her lifetime.

1927- BJ Brimmer Company goes bankrupt, although one source

says it may have remained viable until as late as 1929.

1928- WVJ still working as Treasurer of BJ Brimmer in 1928.

Lives in Boston with mother Myra.

1930- Has two pulp magazine short stories published: “A Girl to her Mirror” in All Story in

February, 1930, and “The Slip-Up” in “Young’s Magazine and Snappy Stories”

in May, 1930. Censused as a renter

living in Winthrop, MA, a Boston suburb, with her mother and lists occupation

as “book writer”.

1932- Winifred wins first place and $25 in the Tony Wons

poetry contest for "Let Us Dream Again". Award presented at the RKO

Keith-Boston Theater and read on nationwide radio. Still living in Winthrop,

MA, as she has since 1930.

1938- Mother Myra Evelyn Williams Jackson dies. Winifred is

living in Boston.

1944- In May, a poetry book entitled Selected Poems by W.

V. Jackson and Ralph Temple Jackson is published in Boston by her niece

named Ralph Dighton Jackson. Ralph Dighton Jackson is the daughter of WVJ’s

brother, Ralph Temple C. Jackson. This

is the 2nd and last of WVJ’s two published books.

1944-1954- Lives at

85 Tyndale, a duplex in the Roslindale neighborhood of Boston, about 4.3 miles

away from brother Ralph and family. Works as a secretary at age 68 in 1944.

1949, 1950, and 1956- A few of her poems whose titles were

not in the early anthologies are published in newspapers, which suggests that

she still was authoring new poems, at least occasionally.

4/19/1959- Deceased. While living at 6 Bellevue St. in the

Dorchester neighborhood of Boston as she had since at least 1957, Winifred

Virginia Jackson was admitted to Boston City Hospital on 4/13/1959. Six days

later on April 19, 1959, at 4 AM, she died of “bronchopneumonia with abscess

formation”, a condition which her autopsy claimed she had had for weeks. She

also had “hypertensive arteriosclerotic

heart disease” and a “gastric ulcer”, and both of these conditions she

had had for years and months, respectively, although not the immediate cause of

death. Her death age is given as 81 years, 1 month, and 16 days which would

indicate she was born on 3/3/1878 (but we know from the 1880 census that she

was born a couple of years before that, with common consensus giving her actual

birth date as March 3, 1876. Thus she died at age 83.) Her “usual occupation”

is listed as “librarian”, but from her timeline you can determine that it

really was secretary/stenographer, with a 5 year period of being treasurer at

BJ Brimmer Publishing Company and an editor at various early jobs. Curiously, she is shown to have no social

security, although SS started in 1935 and she worked at legitimate jobs for

quite a few years after that date. Information to fill out her death

certificate was supplied by Hiram J. Archer who lived at Suffolk University in

Boston, and whose brother, Gleason Archer, founded that university in 1906.

Their mother was Frances Williams. The Archers were from Great Pond, Maine, as

was Winifred whose mother was Myra Williams, and they were distant cousins of

hers. They were childhood friends. Great Pond had and still has many Williams

families.

Interment: Buried in

Manomet Cemetery in Plymouth, Massachusetts

in burial plot 6B owned by Eugene B. Holmes, and occupied by him (d.

1955), his wife (d. 1940), and WVJ (d. 1959).

No other Jackson’s are in this cemetery.

Census records indicate that Holmes lived and worked in Boston, as did

WVJ for most of her life. Both Holmes

and Winifred Virginia Jackson once lived at the same address, 85 Tyndale,

Roslindale neighborhood of Boston, at the same time. 85 Tyndale is a duplex, so

it could mean that they were neighbors. Holmes lived there from 1952-1955, and

she lived there from 1951-1954.

Part

III. Recovered

Articles about Winifred Virginia Jackson

The

following articles supply additional insight into the character and appearance

of Winifred Virginia (Jordan) Jackson. They are presented in the time order in

which they were written. In some cases, the newspaper copies were so difficult

to read that I had to transcribe them.

The 1st

article is the longest and was written while Virginia was still using the last

name of Jordan. Notice that he refers to her as ‘Virginia’, but throughout her

career, others including herself, meticulously refer to her as ‘Winifred

Virginia.’ Perhaps as a child, her family called her ‘Virginia’? (But notice in

the 1893 Great Pond School roster that she is listed as “Winie”.)

The 2nd article’s

author, B.J.R. Milne, had his article appear in the Boston Sunday Post on

1/30/1921, and it is entitled ‘“Spirit” Voice Dictates Poetry.’

The 3rd

article is from the “Hub Club Quill”, June, 1921 issue. It is by Michael White.

It is entitled ‘The Poetry of Winifred V. Jackson’ published June, 1921.

The 4th

article is from the Boston Herald, Dec. 18,1921, entitled ‘Her Verse Wins

Critics’ Praise.'

“The

Girl Who Ran Away” by Bernard Lynch, “National Magazine” 3/1920 to 3/1921

Interview

with Winifred Virginia Jordan by Bernard Lynch

“Vir-gin-ia! Vir-gin-ia! I say, where are you?”

Lay

aside the cares that beset you, and come with me, folks, where are peace and

contentment at the trail’s end. All ye, heart weary, despair not—I have found

the true Arcadia. Draw on “Seven-League” boots and step across into the Valley

of Enchantment.

This is

the journey’s end, so “set” you down and rejoice in the warmth of sunshine that

puts laughter in your soul. Now grim legacies of years take flight, as in your

ears ring the melody of the Headwaters of Union River, while from “way up

yonder” comes the drone of lumberjacks’ songs. For you a welcome is painted in

glowing colors. Freedom—limitless Freedom of the wilderness is yours. Attuned

heart and soul, to the spirit that invests the open places, you’re sitting,

friends, in the scene of the Story’s Prologue.

From the

quaint sign-post at the crossroads you learn that this is “Township 31—Part of

Old Bingham Purchase—Maine.” Down the road a piece, half hidden by foliage, you

trace the outline of an old-fashioned farmhouse. Framed by its vine-clad

doorway stands that emblem of universal love and reverence—a mother. Her

anxious cry echoes from other days: “Vir-gin-ia! Vir-gin-ia! I say, where are

you?” From the hills the call is echoed—then comes silence, and you guess the

truth. Wee Virginia, she of the golden curs and china blue eyes, has “vamoosed”

again.

In the

record once kept by those who tried to rule the willful child we read that each

day, after rocking dolly to sleep and feeding a pet rooster, Virginia’s curly

head would droop thoughtfully while she gazed with longing off to where the

hills rose up to kiss the clouds. Each day eyes, wide and anxious, trace the

wagon ruts that marked the road until it faded from view. Every one whom she

knew to have attained fame had traveled this road; everything that delighted

childish fancy had come from beyond that sky line of hills.

Imagination

thrives best in the open places, and Wanderlust is the heritage of those born

in the shadow of the wilderness. In fairness to Virginia we must be indulgent,

but—Those who ruled the “mansion” were living in a state known as wits’ end.

Dissuasion

in the form of tales of bogies dampened not the ardor of the little wanderer.

Even stone bruises were to her but proud trophies of the romance of getting

somewhere! Virginia, being too frail for chains, and too genteel to be

subjected to the indignity of imprisonment in the garret, the parents

compromised upon an honorable plan.

So came

the day when once more the little gypsy tucked her waxen prototype in bed,

supplied plenty of eats to the overfed rooster, and streaked it for the

hills—for the home of an aunt eight miles distant. We purposely omit the

details of that perilous journey. Enough to record that at sundown the little

traveler arrived, footsore and wary, her gingham frock as mass of tatters, her

curls wildly disheveled, but through the tear stans and black smooches a brave

smiley shining.

Auntie

made the welcome royal. Delicacies reserved for great occasions were brought

forth, and between application of soap and water nods of approval greeted the

story of the Gypsy Queen’s hazardous journey through her dominion. Virginia

enjoyed it like a heroine, and in time fell asleep. Alas, dreams of happiness

can have rude awakenings. Just as Virginia achieved the heights she was shaken

and told to “Get up.” She rubbed her eyes. Had the goblins come? No, it was

only Pa, Ma, and Aunty, but their glances plainly evidenced disapproval.

Without ceremony they gathered her up, carried her to the door, and said

“Look!” As Virginia looked she saw her Pa, his face wearing a grim expression

never there before. He was unloading a doll trunk and doll from the wagon. With

these had come other things—all ready for delivery—all her own property.

“Why,

Mumsey,” she asked timidly. “Why is Pa bringing my playthings here?”

“Because,”

came the serious spoken reply, “you are going to stay here and never go home

again.”

“Never

go home again,” she repeated, wistfully.

Then

came realization of the fearful possibilities of the penalty—evidenced by big

tears and convulsive sobs. “Mumsy, Mumsy,” she faltered, “take me home. Honest

and true. Mumsey, I’ll never run away again.”

There

was something more than was just “plain human” the plea for pity, in the pathos

of the tattered figure, in the tear-wet eyes. Ma and Pa saw it and quickly

gathered their little one in a fond, forgiving embrace.

Again

the scene is the road, deep furrowed, winding back to the Valley of

Enchantment. Majestically occupying her doll-trunk throne sits the little Queen

of All-Out-Doors; in her arms she holds the great Doll image of herself, around

her are grouped the “things” of her own belonging. She is being borne, in

triumph. Home. Here, friends, we draw the curtain on the prologue.

We take

a giant step across the interval of years, and as we read of those to recently

acquire literary fame, into the name—Winifred Virginia Jordan. Yes, our

Virginia, grown up, perhaps richer in worldly wisdom but at heart the same

Virginia, and “still traveling.” Over in New York a publisher highly respected

for judgment, is arranging for a book on Miss Jordan’s poems, selections from

her many magazine contributions.

Editors,

with finger-tips on the pulse-beat of public opinion, are willing to satisfy

that public’s demand for “more,” because they think that in her verse they have

found that quality that lives. Realizing the strong thread of “human interest”

in the character that achieves fame, I accepted with pleasure the editor’s

request to “get an interview.”

The

address, 20 Webster Street, Allston, had been on a number of manuscripts

eventually published in the NATIONAL. I knew the place. I felt that, from

reading her work, I should know the writer. But many mishaps con overtake a

truant fancy. Celebrities, I had reasoned on the journey out, were merely

another species of sheep. The flock might be small and the pasture exclusive,

but—sheep after all, were—sheep!

So I was

not breathless nor palpitating as I rang the bell, prepared to meet a

tortoise-rimmed “intellectual.”

“Miss

Jordan?” I inquired from the smiling vision who opened the portal.

“ That’s

me,” was the cheering response.

“Pardon,”

I entreated,“ I wish to see Miss Jordan—the writer—Miss Winifred Virginia

Jordan.”

“I am

Winifred Virginia Jordan,” came the softly-spoken assurance.

Right

here, had I worn glasses, I would have considered it time to take ‘em off and

remove the rose-tinted lens. Being as how my eyes are cold, cautious, and the

sort that rarely fail in showing things as they really are, I quickly recovered

my lost composure.

“I

regret having seemed to doubt you, Miss Jordan,” I offered, “it seems I have

taken too much—or too little—for granted. Are you willing to receive a visit

from the NATIONAL?”

“Of

course,” she answered with delightful promptness. “Come right in and make

yourself at home. I have reason to be grateful to the NATIONAL. ‘Set’ you down

in this comfy chair, light one of the cigarettes now concealed in your pocket,

and listen while I tell you why you doubted.

“If

folks persist in calling my work psychic,” she continued, “I’m a=going to start

right now and live up to the reputation.”

Reaching

for my cigarettes, I puffed rapidly to create a smoke screen that should

conceal my amazement.

“You

come,” said the voice in the haze, “as others have done, with a look of wonder

on your face. Why? You expect to find a somber bee, when there is but a

care-free butterfly. As you paused at the door, you found it difficult to

reconcile a brass head, a pink complexion, blue eyes and a Sunny-Jim smile with

aught that is literary. For the moment I reminded you of others you have met—the

dizzy soubrette of the wiggly chorus and the lady who adorns the tooth paste

ads with her engaging smile. Then you quickly changed you opinion, and was

ready to apologize for such thinking.

Since when, after retreating behind your smoke curtain, you have decided

to start all over again. Well, I’m not blaming you. They’re all like you--at

first.”

I sat

straight, took a firmer grip on my idle pencil, and stared astonishment. Then,

as if she had willed silence, I waited while her glance traveled to the window

and over the autumn foliage, perhaps to find a new image in the wondrous

weavings of brown and gold. Knowing no photo would do her justice, I took

advantage of the lull, and wrote: Blond,

beautiful and real, rare as her own creations, and equally as wonderful, are

the heavy coils of hair circling a small and graceful head. A veritable crown

of glory it is, with lights upon it that quicken the imagination and play

tricks with the fancy, as it radiates changing glows of burnished bronze,

rose-hue and gold. Yes, hair capable of making any man romantic and any woman

envious. Nose, a wee bit retroussé; carmine lips that reveal teeth even

beautiful and white; skin like alabaster with shell pink tinting, eyes indeed

blue and bonnie. Tall, graceful, with quiet dignity in every movement, a figure

whose lines are marked with almost breathless precision. Good, very good to

look at.

Young,

quite young for one to wear the crown of literary achievement, with a

vivaciousness that ever and anon proves evanescent, overcome by serious moments

Spirituelle and—oh, just the living likeness of the heroine of a million dramas

and a billion books of fiction.

“Your

lumberjack poems are much admired for realism,” I remarked, since her eyes

again invited me to speak. “The inspiration for them—“

“Came

from the voice that whispers words in melodies in my ear. The messages—call

them inspired if you will—are written as received, without revision. I am only

the medium through which they find the light.

“But,”

she added reminiscently, “you must let me follow the read back to a little

village of twenty-one houses, settled in 1811. Father was a lumberman, everyone

was either that or a farmer. All around lay the wilderness, the nearest

neighbor was a mile distant. In a corner of the little old red schoolhouse I,

at the age of two, occupied a wee chair. I see Pa’s hound dogs and the bear he

chained to a chimney in the cap store house. I’m being taught Pa’s first

lesson—how to shoot a Winchester.

I being

so tiny, he made a ‘contraption’ to rest it on. Days, short as hours, are

crowded with thrills. I’m camping, fishing, canoeing on Jo Merry Lakes;

tramping the big woods, always roaming, and always in my ears, always,

‘Vir-gin-ia! I say, where are you?’

“Lazily

busses the cant-dog saw mill, loudly pound the logs on the river, resonant are

the voices of the loggers, their sunshine and shadow are mine, too. Night

glowing camp fires, their witchery heightened by a gypsy circle spinning

fictitious truths. And, when the heart warmed, and the soul developed, songs of

yearning came freighted with the fragrance of romance—reaching you with the

incense of burning logs of pine and hemlock. No, it is not strange. The voice

that whispers knew me then.”

The eyes

were eloquent as she completed the picture, wherein could be traced “Driftwood

and Fire,” “Ellsworth to Great Pond,” “The Song of Johnny Laughlin,” “Larry

Gorman, Singer,” and “Joe,”—her poems of woods and lumber-jacks.

Then,--the

voice soft, the eyes wistful—“To you, perhaps a simple setting, without appear.

To me—home.”

“There

were days of disappointment,” I suggested.

“Many

filled with longing—only one of disappointment.”

“And

that?”

“Was

when a good-for-nothing neighbor found me on the trail to the fishing hole and

out of sheer cussedness stuffed my mouth with wiggling worms.

“I

cried—cried until I reached home. That night I lay awake dreaming of

vengeance.”

As she

spoke there crept into her eyes a fire, her chin was firm set, her face looked

grim, and living agin in spirit were her illustrious ancestors, General David

Cobb, Dorcass Cobb, John Rogers of Sudbury and Thomas Cobb----the lien

extending back to those sturdy pilgrims who came, fought, and conquered.

“Next

day,” she continued, “I borrowed Pa’s shotgun and the ‘contraption.’ Arrived at

the same place on the trail to the fishing hole, I set both in position and

then, with my finger where it could easily touch the trigger, I waited.

“That

mean man proved meaner still. He did not pass that way again, the vigil kept up

until the sun went down. That was my day of disappointment!”

Though

fascinated, I could remain no longer. Summing up I wrote, Complex of character,

with moods and vagaries as difficult to analyze as her work. An impressive

personality, not easy to forget, and in which are mingled the sparkling

shallows of simplicity and great depths of philosophy. Withal, delightfully

refreshing, charming in manner, and true to her ideals. The little, whimsical

smile returned as I arose to say good-bye. She bowed her adieu with such

elegance of grace that I felt as if taking leave of an old friend—on whom I had

known ages ago.

Back at

the office I recall that the name—Winifred Virginia Jordan—was more than a

euphony that haunted. It was associated with big things. As one famous critic had phrased: “The author

of these poems has escaped the contagion of the times and has been gifted with

a power of song whose type is in a measure absolutely unique. If, as we have abundant reason to believe,

the function of true poesy be to wake the fancy and delight the imagination

with a combination of sense and sound well adjusted in delicate harmony, then

we have reason to look upon Miss Jordan as one whose claim to the title of poet

is more than ordinarily strong and merited.

Lyric beauty and harmony of exquisite development pervade her poetry, while

the heavy commonplaces of the average versifier are notably absent.”

Caption under picture: "Winifred Virginia Jackson of Allston whose poems almost write themselves in a mysterious way."

“Spirit“ Voice Dictates Poetry” by

B.J.R. Milne

Jan 30, 1920, Boston Sunday Post

Is this

a “Fairy-Led” poet? Who can answer?

Winifred

Virginia Jackson of Allston writes poetry as it never has been written before.

In fact,

in one sense, she doesn’t write it. She just takes it from dictation. Who

dictates it to her? Nobody. And yet, she

doesn’t think of the verses herself. She hears them—actually hears them. It is

as if a voice lived in her brain, and recited the entire poem to her, beginning

with a bare title that meant nothing to the writer and rattling off the verses

stanza after stanza—sometimes so fast that it’s all her pencil can do to keep

up with the words!

“Is it

fairies?” I asked her. It’s hard to think of an absolute abstract being

responsible for an action, and, while only imaginative people now believe in

fairies—more’s the pity!—they have some sort of substance in them. At least,

it’s far easier to picture a fairy talking to you, than to hear it from

Mr. Nobody.

“Fairies?- - -

-Why----why---I’m sure I don’t know. I’d never thought of it that way.” Miss

Jackson seemed much bewildered. She wanted to tell me just what she thought was

what, but it was difficult to explain.

She went

on: “The voice just tells it all to me. Take “The Fight,” for instance. It

started that way. The voice said “The Fight.” So I wrote the words down. And

then, quickly, smoothly, came the story

of Larry and Mike of the lumber camps.”

To give

an idea of that rough-and-ready verse, I’ll quote a bit from “The Fight”:

An’ Mike

were gittin’ groggy,

But he

pounded like a bull!

An’ we

could see that Larry

Ware

a-hevin’ quite a pull!

The he

backed and broke guard steady,

(Hell!

But Larry looked damned raw!)

An’ on

his whole weight drawin’

Up an’

landed on Mike’s jaw!

“Her

poems of the lumber jacks are ??? that—rough, rollicking. Some are reminiscent

of service, some are chantees, with a music loved by the hewers of wood in the

Maine forests. For Miss Jackson comes from Maine. Her father was a lumberman.

Early Became Crack Shot

As a

girl she lived on a farm a mile from her nearest neighbor. She went to the

“little red schoolhouse” which every country lad and lassie knows. Her first

recollection is of “hound dogs” and of a bear chained to a chimney in a large

shed where flour, grain and ??? things were stored for use in the lumber camps.

“The

first thing my father taught me,” She smiled, “was how to shoot a Winchester

rifle. Since I was too young to hold a rifle, he made a “contraption” for me to

rest the rifle on.”

Which

made her think of the one day of almost unbearable disappointment. She laughed

and made a faint grimace. “Once a good-for-nothing neighbor found me on the

trail to the fishing hole and out of sheer cussedness, stuffed my mouth with

wriggly worms. . . “

“Nasty!”

I commented. “What did you do about it?”

“I

cried—cried until I reached home. That night I lay awake dreaming of

vengeance.”

You can

imagine the determination of which Miss Jackson is capable. She is a direct

descendant of Frances Dighton Williams, wife of Richard Williams who was a

relative of Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island. She is also a direct

blood descendant of Oliver Cromwell, England’s liberator, whose

great-grandfather was another earlier Richard Williams, who changed his name to

Cromwell in order to inherit an estate. In her there is the spirit of Thomas

Rogers, of Dorcas Cobb and General David Cobb, first agent of Maine of the

Great Bingham Purchase.

No Man Came to Shoot

“Next

day,” she said, “I borrowed pa’s shotgun and the “contraption.” Then I went up

to the same place on the trail to the fishing hole and set up my artillery. I

kept my finger very near the trigger.

“That

mean man was even meaner still. He didn’t come, and I hadn’t the chance to

shoot him. That was my day of disappointment.”

I can’t

say that Miss Jackson struck me as being a young lady homesick for Maine, but

the Voice at least must have been “homin’” for the banks of the Guagus when it

dictated this verse to her:

I wish,

oh, I wish I was back home again!

I’d jump

for my turn at the plow;

I’d rake

up the hay with a hip-hip-hooray

And I’d

fork it away in the snow!

And if,

as I wish, I was back home again,

“Tis

never again would I roam!

I’d care

not one jot for an ????b’s fine lot—

For

there ain’t nothin’ nowhere like home!

And

herself? Let’s have her own description of herself first: “. . . A

brass head, a pink complexion, blue eyes, and a Sunny Jim smile. .

. .the dizzy soubrette of the

wiggly chorus. . . .the

lady who adorns the toothpaste ads.”

At

least, that’s how she believes other people see her.

Is a Beautiful Girl

She’s

beautiful. I think even a critic of poetry would agree upon that point. Her

head is burdened—a harsh word, perhaps—with a mass of bronzy-gold hair. That’s

why she calls it “brass.” Her complexion is pink, as she says, though an artist

would not use such a flat statement. As for her smile, very likely it is a

Sunny Jim smile, as she says, but I don’t know what s Sunny Jim smile is like.

I’d call it, rather , a dubious, uncertain smile—a smile that told you she had

a great deal to say to you, but that she didn’t know just how or where to

begin.

But,

really, the only way to tell what she writes is to quote from her writings. And

always this point should be born in mind—the Voice—the Voice that first spoke

the lines. . . .

I called

and called unto the world.

I, Caza,

the Dancer;

But not

a breath of music stirred

In

answer!

And then

I heard a pretty tune

All

joy???? and laughter,

But I

had grown too old to dance

On

after!

Can you

believe that last summer, while in Maine, Miss Jackson wrote 49 poems in three

days, at three sittings? It is all but unbelievable! And yet she told me so,

quite naively. There was absolutely no reason for exaggeration. A poet is not

judged by the number of poems produced in a given time. There are few poets

today who would date to confess such a prodigious output. Critics call them

mere mechanics.

Why she Uses Pencil

But,

Miss Jackson reminded me, “It wasn’t I who really was responsible for the

verses.” The Voice. . .

. Her pencil worked fast those

three days. “I can’t use a typewriter except to transcribe my handwriting,

because the noise deafens the Voice.”

And in

those few weeks spent in Maine, she wrote 96 poems. “The Mirror” is an example

of the mystic in her work.

Last

night I looked into my mirror;

I dare

not look again;

I dare

not see my heart so sick

And

ghastly gray with pain!

I cannot

look into my mirror,

For

there my heart looks out

Its

deathbed where it weeps and writhes,

But

cannot turn about!

Truly,

her range is a sweeping arc. . .

. .His styles or moods—whatever

the-man-who-knows would call them. Cold she attain such broad vision without

the Voice?

THE HUB

CLUB QUILL, Vol. XIII, June, 1921, No. 2.

The Poets of Amateur Journalism

The Poetry of Winifred V. Jackson

Bliss

Carman, in a beautiful poem, published some years ago, and extensively quoted

in this country and in Europe, treats April, seemingly the favorite month of

the poets, partly as follows:

With the

sunlight on her brow,

And her

veil of silver showers

April,

o’er New England now

Trails

her robe of woodland flowers.

Nobody

can deny the haunting magic of these lines, and yet, April, with the “sunlight

on her brow,” wearing a “veil of silver showers” and trailing her “robe” of

“flowers,” are pictures that have been used many times before and since Mr.

Carman was born, Miss Winifred Jackson, too treats of April in her best and

most characteristic vein when she says:

I would

out to April weather;

To the

sunlands in her train,

Laughing,

while the sunbeams tether

Up the

yellow wraiths of rain.

We

realize perfectly that in putting these two extracts before our readers we are

comparing a poet, recognized almost universally, as a rare genius of song, with

one practically unknown in the literary history of our day. Yet, who can deny

the strong outlines, the startling boldness of conception , and the easy grace

and flow of Miss Jackson’s lines? The very spirit of April in in her touch.—the

alternate sun and shower, the big, bounding elastic delight of the open field,

and then masterly stroke of genius contained in the last two lines,--bold,

original and vivid as a flash.

It has

been said in the professional press that a “spirit voice” dictates to Miss

Jackson the poems she writes,--that she is merely the instrument that gives out

the unconscious melody. This analysis is not even half true. The “spirit” that

possesses her at such times is the same “spirit” that inspired Shelley when he

wrote the Skylark, Keats when he gave the world his ode to a Grecian Urn, Byron

when he conceived that magnificent Fourth Canto of Childe Harold,-- the same

delusive and indefinable ”spirit” that

inspired Wagner when he wrote the Pilgrim’s Chorus; the same “voice” that Guided

the hand of Raphael, or moved the chisels of Phidias or Praxiteles. It is the

old old story of mere mortal trying to bring down to the level of a common

understanding the promptings of genius.

In

ordinary occasions when we are told by “poets” that a “spirit voice” prompts

their writings, as a mere natural precaution of self-preservation we try to

move away to a safe distance before he or she insists on reading them. But we

are surprised to find, despite the alleged “spirit voices,” that Miss Jackson’s

poetry owes not a little to art. Some of her poems are masterpieces in plan and

design. If a “spirit voice” ever dictated a poem it would be “without form and

void,” it would have neither beginning, middle nor conclusion, and it may

fairly be asserted that there is not one solitary instance in all literary

history where the words did not come from the conscious or subconscious

inspiration of the writer.

Miss

Jackson’s rare gift consists in seeing pictures, beautiful, illuminating, and

startling, where nothing is visible to the ordinary vision. Her poems are often

mere fragments, seemingly broken and incomplete, yet withal revealing an

insight, a vision, reprinted from the “Boston Transcript” in the Bonnet, some

time ago reveals her at her best as a poet and an artist. Her them, too, is

admirably chosen as giving her fancy freedom and scope, and her treatment of

the subject is superb. We have space only for one verse. The spirit in the

sea-shell asks the listener to put her ear to its heart and “listen well”--

And hear

that little summer breeze

That soothes

the work-worn wings of bees;

The

chimney’s song on winter’s night,

The

fire’s delight,

The

owlet’s tune

In

moon-mad June,

The

whirl and whir of Things that BE

From

tiny acorn to the tree.

Miss

Jackson’s poetry is essentially the poetry of inspiration. The painful process

of elaboration and elimination are things that do not trouble her. There is

visible in her poetry no straining for strong lines, no fashioning words on the

basic thought of another, no painful alliteration for polished phrases. What

she partly gives and partly withholds is herself. Her symbols,--for her Muse at

its best is purely symbolic,--originates in her subconscious experiences of

life in its many moods,--sad sometimes, gay often, or wild with the thoughtless

abandon of a child. She is never so philosophic as when she throws philosophy

to the winds. The lullaby of the murmuring waves; the dense wood transformed by

the magic of moonlight into a fairyland; the scurrying cloud across a purple

sky; the sighing of the wind among the trees; the perfume of leafy June;--these

are her themes, but deeper than these, is the half concealed and half

articulate sadness—the eternal sadness of genius, struggling for, and denied

expression. We say “denied” advisedly, for Miss Jackson has not yet come into

her own. Her poetry is great less in performance than in the promise. She has

written mostly of external things; in a few pieces—lines—mere glimpses we get,

it is true, of the poet, and these are invariably her best.

Sometimes

Miss Jackson, prompted by some inexplicable urging, produces what may, for a

better name, be described as a “silver lining” poem. Cults, magazines, and even

religions in our day have been devoted to produce a perfect world by the

mechanical smile, the glad hand, and the stereotyped advice to ignore the

shadows of life, to forget trouble, and to cry sunshine when there is no

sunshine. Of course the whole performance is artificial, stunted and untrue. It

has never inspired a great poem and never shall. Writers of genius have essayed

the glad tidings and have signally failed, and of course Miss Jackson could not

be expected to succeed where success is a poetic sense is impossible.

We are

not privileged to touch on the professional aspect of Miss Jackson’s work. Her

first poems appeared in amateur papers and to the credit of some of our best

critics she was at once recognized as a poetic genius. She is young in years

and is devoted to her art. She is wide read and has acquired a philosophy of

life. She has already attracted the attention of professional critics and

another decade should write high on the list of the poets of our day the name

of Winifred Virginia Jackson.

MICHAEL

WHITE

Part IV. Recovered Poems- Listed roughly in the order of their

discovery

WINIFRED VIRGINIA JACKSON’S WORK

- Ellsworth to the Great Pond

- The Tricksy Tune

- Eyes

- Fear-Flame

- Black Aikens Lot

- And One Is Two?

- Brandy Pond

- Hoofin’ It

- Deafness

- Eves

- Dust Song

- Fear-Flame

- Earth Breaths

- Finality

- Hands

- Heritage

- A Witch’s Daughter and a Cobbler’s Son

- Monday, Wash-Day

- Makin’ Rhymes

- On Ellen Going Wrong

- On Meeting Father Goose

- Pitch O’ Pine Sonnets, 1,2, & 3

- Poor River Drivers

- Red Winds

- Scuffled Dust

- She Told Mary

- The Sin

- Threads

- Strange Paths

- Under-Currents

- Weights

- Wimin’s Work

- Sunrise at Cooper

- April

- April Shadows

- In April

- In Morven’s mead

- The Night Wind Bared My Heart

- On Shore

- Who Will Fare With Me?

- Galileo and Swammerdam

- Loneliness

- Values

- The Bonnet

- Driftwood and Fire

- Lady Summer

- The Musquash

- The Song of the Sea Shell

- Atavism

- Cross-Currents

- The Farewell

- Her First Party

- Bobby’s Wishes

- The Howl-Wind

- Baby Bluebird

- Fallen Fences

- Life’s Sunshine and Shadows

- The Northwest Corner

- The River of Life

- A Merchant from Arcady

- Waiting for Betty

- Haying (found in 1949 West Virginia newspaper)

- Fragment

- Fragment from The Fight

- Caza, the Dancer

- The Mirror

- The Purchase

- Brown Leaves

- The Cobbler in the Moon

- In Moreh’s Wood

- On Shore

- Fragment

- The Pool

- The Vagrant

- Sea-Winds

- Fragment

- Have You Met My Buddy?

- There’s a Way

- When the Woods Call

- Dora of Aurora

- A Lad o’ Sixty-one

- Something Back in April

- September (found in 1956 Boston Herald)

- Midnight at the Mill

- Tenants

- Nearing Winter

- I Knew a Tall Lad Once

- Smoke

- Mary, Queen of Scots

- Death Is a Moment

- Gray Man

- The Mould Shade Speaks

- Door

- To You

- Workin’ Out

- The Token

- Assurance

- It’s Love Time

- The Song of Johnny

Laughlin

- Larry Gorman, Singer

- The Call

- John Worthington

Speaks

- Insomnia

- Contentment

- Song of the North

Wind

- The Night Wind

- How Fares the Garden

Rose

- List to the Sea

- To a Breeze

- Songs from Walpi

- The Duty

- Dear

- Absence

- Chores

- Faith

- Oh Where Is

Springtime?

- The Singing Heart

- When the Sea Calls

- The Time of Peach

Tree Bloom

- Oh Rose, Red Rose

- To England

- Be Tolerant

- Alley

- Lord Love You, Lad

- The Last Hour

- My Love’s Eyes

- Ole Gardens

- Longing

- The Death-Watch

- Love’s Magic

- I Have Tasted of the

Waters

- Adoration

- White Star of Love

- A Wind Waif

- The Rose of

Friendship

- But There Is Love

- Days of Laughter

- Difference

- The Discontented

Daisy

- Do You?

- Fog

- A Hope

- I Would Out to April

Weather

- The Jester, Fate

- Joy

- The Lament of March

- Outdoors

- To a Decoy Duck

- What’s More

- Smile

- O’ Heart of Me

- Joe

- What More

- In the Shade

- Smiles

- The End

- Booey’s Wishes

- How Fares the Garden

Rose?

- If You But Smile

- When You Went

- John’s Mary

- Quills

- In the Shade

- It’s Lovetime

- A Girl to Her Mirror

(published 1930; short story)

- The Slip-Up

(published 1930; short story)

- Let Us Dream Again

(1932 poetry award)

- In a Garden

ELLSWORTH TO GREAT POND

Drink hard cider, swig hard

cider,

Swill hard cider, Boys!

Throw yer spikers, throw yer

peavies,

Beller out yer noise!

Grub in Waltham, drink in

Waltham,

Slogger up an' down!

Hide ye slat-faced, heathen

Christians,

K-J's crew's in town!

Drink hard cider, swig hard

cider,

Whoop 'er up, O Boys!

Hell' s own roarin', cant-dog sawmill

Can't make half our noise!

Sling yer spikers, sling yer

peavies,

Put yer head to use!

K-J's waitin'! K- J's watchin'!

King o' old K. Spruce!

THE

TRICKSY TUNE

The Hired Man Speaks:

"He never spoke a civil word

To her; it was his rule

To snarl or shout; his best for her

Was 'Mooncalf, dolt an' fool!'

" The Story: The house was built back from

the Road. ;

It stood there grim and gray

And silent, 'mid great aspen trees

That quivered night and day.

The Road was narrow; old stone walls

Arose on either side

Begrudging from the farm the land

The roadbed had to gride.

And she had lived with him and drudged

For over twenty years;

He drove her on, from harrowing

To breaking in the steers.

At first when she was called a fool,

A hurt look dulled her eyes,

And she would slip off by herself

And have her little cries.

But once he caught her; after that

She never dared to cry;

The days seemed all alike to her

That wearily went by.

And often, when he snarled and cursed,

She played a little game;

She tried to make believe that he

Had called her some sweet name.

Then one day came a tricksy tune

That hummed within her head;

In spite of all that she could do

It held the words he said.

She heard the song and shuddered at

Its "Fool, dolt, fool, dolt, fool!"

The while she gripped her hard, worn hands

And drabber looked and cool.

And this kept up for weeks ; she worked

With hope to still the song

By weariness ; it sometimes went away

But would not stay for long.

When evening came, he sat about

The kitchen while she rid

The sink of dishes, nagging her

Through everything she did.

And then he'd go to sleep and snore,

Sprawled in the rocking chair;

The light shone on his long, gray beard

And bristling, grizzly hair.

And so he lolled ; she mended, darned,

The while she scarce could see;

The song beat time within her head

That ached unceasingly.

A day came harder than the rest;

He snarled at her and raved,

And of the nagging words he knew

There was no word he saved.

night came with the supper ; wash

Of dishes in the sink;

And afterwards his snores ; her song;

She ceased to try to think.

The Hired Man Speaks:

"I found him crooked upon the floor;

The ax was sharp, for he

Had sharpened it that day an' whet It sharp as

it could be.

She didn't notice me; she sat

As white's a sheet, but cool,

An' hummed a song: the words want much,

Jest, 'Mooncalf , dolt an' fool!' "

EYES

When life is very lonely

I close my eyes and go

Across a field and up a hill,

A way I know;

And there I find a garden

With a little house in it,

And both are wistful whispering,

"Come in and sit !"

Then you come, always singing,

On down the garden's walk,

And we, in white front doorway, stand

And softly talk. I often light a candle,

In my small sitting-room,

To show you some new picture or

A bit of bloom.

And all our time together

You love as much as I :

But, oh, my open eyes that watch

You passing by!

HOOFIN'

IT

Pork an'

Beans an'

Apple pie!

Doughnuts,

Swagen,

By Gor-ri!

We'll hit

Great Pond

By an' by!

I am but a river hog,

River hog, river hog!

I am but a river hog

Hoofin' it to Great Pond!

Ellsworth is a meachin' town,

Sick'em town, lick'em town,

Ellsworth is a meachin' town,

Ring-a-round-a-rosy!

Ellsworth has a pretty pound,

Pretty pound, pretty pound,

Ellsworth has a pretty pound --

Pin on me a posy!

Waltham has no use for us,

Use for us, use for us;

Waltham has no use for us

When our heads are groggy!

They wun't give us feather beds,

Feather beds, feather beds;

They wun't give us feather beds --

No, we bunk with hoggy!

K-J he don't give a damn,

Give a damn, give a damn;

K-J he don't give a damn

If in hell we're seated!

Great Pond's miles an' miles away,

Miles away, miles away;

Great Pond's miles an' miles away

But the soup is heated!

K-J's waitin' there for us,

There for us, there for us;

K-J's waitin' there for us --

He's a damn good-fellow!

K-J makes us pick our shirts,

Pick our shirts, pick our shirts,

K-J makes us pick our shirts --

Makes us work O hell-o!

I am but a river hog,

River hog, river hog,

I am but a river hog

Hoofin' it to Great Pond!

Pork an'

Beans an'

Apple pie!

Doughnuts,

Swagen.

By Gor-ri!

We'll hit

Great Pond

By an' by!

BLACK AIKEN'S LOT

I took a walk one

gloomy night

Across Black Aiken's Lot:

And lost I was and cold I was

When, lo, I spied a cot!

A candle lit was goodly sight

As I drew nigh the door,

Where such a welcome as I reeved

I ne'er had reeved before.

A Dame was there in swaiping gown,

With twenty padded curs

That edged a curious row around

And growled when she said, "Hers!"

"Sit down, Good Sir," the Beldam cried,

"Come, sit thee down, I pray!"

"A willow was I and fell my leaf!"

A voice warned, thin and gray.

"Then broth, Good Sir!" but a wooden spoon

Shrilled high within the pot,

"He cut off the head of the golden hen

Beside his father's cot!"

The Beldam turned to a peeled stick

That in a corner stood:

She lashed the curs as it loudly spoke,

"His navel blessed my wood!"

Then flung she trimmings of aged nails,

And a hundred whited teeth,

But open swung the heavy door

And I sped across the heath!

And when I'd found my way to town,

And told my story fair,

Old Luke spat East, North, West and South, --

"Black Aiken's Lot is bare."

AND ONE IS TWO?

Who calls? I

cannot say,

Nor do I care -- nor care!

Old Mother Hubbard went to her cupboard

And found that the cupboard was bare.

The mouldering folk may call?

Ah, then, an end to songs!

Come to our wounds with cool powder and poultice,

And a gold pen to right our wrongs.

Who calls? And one is two?

The cat is dead -- was killed!

Yellow canary will sing on the coffin

And live in the house -- one will build!

BRANDY POND

Come all you jolly river boys and join me while I sing,

A song of days of long ago that recollections bring,

And you will hear how Brandy Pond was named an honoured name,

And Johnny Williams of Great Pond was given of the blame:

Though there was Judson Archer and J. Gooch of Yarmouth, too;

And Hopkins, up from Ellsworth, and the son of Donkey Drew,

As went into the wilderness to locate of the pine,

The punkin, and the hemlock, on the old Lute Jackson line:

O brandy is the life of man,

Brandy! Johnny!

O brandy is the life of man,

Brandy for our Johnny!

I drink it hot, I drink it cold,

Brandy! Johnny!

I drink it hot, I drink it cold,

Brandy for our Johnny!

I drink it new, I drink it old,

Brandy! Johnny!

I drink it new, I drink it old,

Brandy for our Johnny!

We viewed a pond a gliffy's thrice,

Brandy! Johnny!

And set to cross it on the ice,

Brandy for our Johnny!

Close by the shore an air-hole hid,

Brandy! Johnny!

It almost caught our noble Sid,

Brandy for our Johnny!

But Johnny in the water went,

Brandy! Johnny!

As quick as that false ice it bent,

Brandy for our Johnny!

And in that hole our bob it fell,

Brandy! Johnny!

And down our grub it went as well,

Brandy for our Johnny!

On top of Johnny, cold as ice,

Brandy! Johnny!

We hauled John out but he wan't nice,

Brandy for our Johnny!

Our keg of brandy did not sink,

Brandy! Johnny!

It floated on that dangerous brink,

Brandy for our Johnny!

We pulled that keg out, brave and bold,

Brandy! Johnny!

For cold as Greenland grew the cold,

Brandy for our Johnny!

No tun nor dipper had we then,

Brandy! Johnny!

To drink us from, us freezing men,

Brandy for our Johnny!

So we took knives and cut a bowl,

Brandy! Johnny!

Down in that ice, and round that hole,

Brandy for our Johnny!

We lay us down and drunk our fill,

Brandy! Johnny!

And drunk us to the very gill,

Brandy for our Johnny!

O brandy is the life of man,

Brandy! Johnny!

O brandy is the life of man,

Brandy for our Johnny!

I drink it hot, I drink it cold,

Brandy! Johnny!

I drink it hot, I drink it cold,

Brandy for our Johnny!

I drink it new, I drink it old,

Brandy! Johnny!

I drink it new, I drink it old,

Brandy for our Johnny!

So, here I end the song I sing of that brave company,

A song that I have sung to you like one I learned at sea,